Trickle-Up Innovations — Success Stories From the World’s Five Largest Slums

Urban planners and development scholars continue to tout slums as hotbeds of innovation. While there’s no whitewashing the harsh realities of life in the world’s most vulnerable communities, cities of the future could benefit both informal settlements and the rest of society by supporting trickle-up innovations at their source.

Guy Liechty

4/27/202311 min read

The term ‘unplanned’ carries a negative connotation — implying disorganization, uncoordinated growth, and unqualified claim to the development process. It assumes that unplanned settlements and slums will face insurmountable barriers to their growth over time, and omits from its consideration the cohesion and generative potential of the communities that inhabit them. Constrained by a lack of space and resources yet unfettered by zoning laws and other regulations, slums have shown an incredible capacity to adapt despite the odds.

It’s not that slums aren’t planned, it’s that planning is decentralized and iterative. Residents, businesses, and community-based organizations unite and interact as nodes of a complex and constantly evolving organism — like a mycelium network, these communities allocate resources and space in ways that are often more utilitarian than in more affluent postal codes.

A small crowd of people in front of shops in the Dharavi slum, Mumbai, with a 3-story building under construction in the background (Image Source)

Orson Welles once penned, “The absence of limitations is the enemy of art.” While there is no glossing over the unforgiving realities of life in the world’s most vulnerable communities, the lack of resources in slums and other informal, decentrally-planned communities directly contributes to their resourcefulness. The lack of government regulation in these areas has allowed for remarkable trickle-up innovations which — if health and safety standards were properly safeguarded through technical or systemic interventions — could be replicated throughout mainstream society.

Half the size of Central Park, Dharavi supports upwards of one million people in something of a self-organized economic zone, a billion-dollar per annum informal economy without — for better and worse — government regulations in the form of taxes, intellectual property rights, or other forms of state control. Over a billion people live in slums; the UN forecasts that by 2030, three billion will be in need of adequate and affordable housing in these areas.

Makoko is an informal settlement on the coast of Lagos, Nigeria. One-third of the structures are built on stilts jutting into a lagoon (Image Source)

Residents of informal settlements are not without purchasing power. They are willing to pay for services that safeguard their livelihood productivity or infrastructure investments — housing, power hookups, clean water, and sanitation facilities — particularly when governments fail to provide these or do so inadequately. Innovation happens from both within and without, in the form of organic innovation or through interventions by social businesses, NGOs, and private companies that recognize an unmet need.

This article highlights innovations from the planet’s five largest informal settlements and suggests ways in which these might be applied in more “developed” nations. Rather than investing in resettling residents further and further from the center of cities, local governments would do well to invest in slums where they are — both in regard to basic services residents require (access to decent housing, affordable healthcare, and pathways to land tenure) as well as the services slums provide to the local economy.

Dhobi Ghat in Mumbai is an oft-cited business example of efficiency in the homespun laundry industry (Image Source)

Innovations From the World's Five Largest Slums

Low-cost sanitation in Orangi Town, the most populous slum in the world (Image Source)

Orangi Town — Karachi, Pakistan: 2.4M people

Sanitation and Sewers — The Orangi Pilot Project (OPP)

Background:

Located on the outskirts of Karachi, Orangi town began to attract a massive influx of residents in the early 1970s after East Pakistan’s war of independence. Due to a ballooning population and only partial provision of basic infrastructure and services by the municipal government, sanitation became a salient hazard of daily life.

Bucket latrines and soak pits served as sewers, endangering both residents’ health and property. In 1980, the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) — a local NGO serving the needs of local residents — began work on an affordable sanitation system.

Innovation:

After a year of feasibility research, the OPP developed a plan to implement a settlement-wide sewer system using locally-trained masons and simplified steel molds for public latrines and sewer pipes. The project was funded by Orangi Town residents at a cost of 1000 rupees (about 30 USD) per household, and remains a functioning sanitation system today.

Lessons:

Slums have purchasing power and relatively low overhead costs.

Where land rights are assured, slum households will invest in their own best interest — and that of the greater community — in regard to public health and sanitation interventions.

When self-organized outside the scope of government or private contractors, costs were less than a quarter of the standard contractor rates.

Once a shanty, Neza has bloomed into a success story in grassroots organization and community development (Image Source)

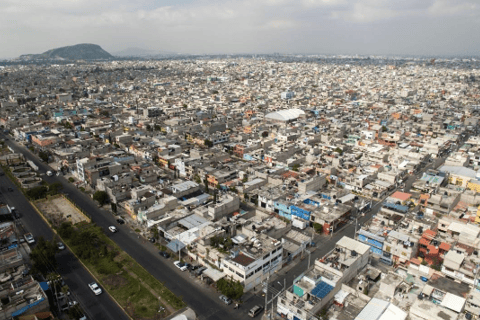

Neza — Mexico City, Mexico: 1.2M people

Informal Zoning — Community Organization

Background:

Neza, short for Ciudad Nezahuyalcoyotl, no longer resembles a slum in the conventional sense. Once a shanty settlement built on the salty remains of a desiccated lake, Neza is now considered in many ways a success story — a cultural hub for anti-establishment rock culture, artistic expression, and political unity. While the area is still considered dangerous, the area’s residents have a tremendous amount of pride in where they come from.

Innovation:

Neza’s rise as an urban success story was made possible by decades of tireless activism and community organization. Having been sold land without formal titles, Neza’s residents began petitioning the government for a means to formalize ownership of land titles beginning in the 1970s. It wasn’t until fights between residents and land barons broke out that the government intervened — at which point politicians realized that thousands of votes were worth more than land barons’ money.

Multi-use, informal zoning still characterizes Neza today — micro-entrepreneurs use their homes as shared workspaces, contributing to the local economy while utilizing space more efficiently.

Lessons:

When organized, slums carry political power

When zoning happens organically, space utility is maximized

Slums are more than a transitional space — they have a profound impact on the development and character of a city

Recycling is a way of life in Dharavi (Image Source)

Dharavi — Mumbai, India: 1M people

Circular Economy — Waste Management

Background:

The most densely populated place on earth, Dharavi is home to over a million people occupying a mere two square kilometers. Founded on swampland in the 18th century, Dharavi is now a teeming hub of industry in the heart of India’s commercial capital. Its efficiency in waste management and recycling is studied in management and urban planning schools the world over.

Innovation:

Dharavi contains over 15,000 single-room factories employing 250K people in its billion-dollar per year recycling industry. While health and safety standards are far from ideal, Dharavi has been a living case study in the circular economy since before the term gained popular recognition. By some estimates, Dharavi recycles 80% of Mumbai’s post-consumer plastic.

Lessons:

Waste management can be profitable

Ragpickers and those at the base of the informal waste management chain receive a disproportionately small portion of the proceeds, while trash barons reap the lion’s share of rewards

Private industry can solve municipal problems, when not restricted by zoning or regulation

The Community Cooker in Kibera (Image Source)

Kibera — Nairobi, Kenya: 700K people

Waste and Clean Cookstoves — Community Cooker (Planning Systems Services Ltd)

Background:

The largest slum in Africa, Kibera is home to nearly three-quarters of a million people who traditionally use charcoal or wood to heat water or cook food. Recognizing the adverse health effects of burning charcoal and the abundance of trash in Kibera, Planning Systems Services Ltd. Launched the Community Cooker to serve as community waste-to-energy infrastructure for Kibera residents.

Innovation:

The Community Cooker produces enough energy to cook 472 liters of food and heat 4,800 liters of water — serving 2,100 residents — in a 12-hour period. It burns up to two tons of rubbish per day, of any type. The solution uses simple technology to generate energy from waste, providing energy to residents in proportion to how much waste they collect.

Lessons:

Waste is a resource

Incineration as a waste management practice can have local, rather than larger municipal, applications

Waste management is improved by establishing a clear and direct link to a community benefit

The Empower Shack Prototype by Urban-Think Tank and ETH Zurich (Image Source)

Khayelitsha — Cape Town, South Africa: 400K people

Affordable Housing and Land Tenure — Empower Shack (Urban-Think Tank, ETH Zurich, Ikhayalami NGO)

Background:

While South Africa includes a right to adequate housing within its post-apartheid Constitution, the country’s high housing prices and restricted access to finance have left 7.5 million South Africans to live in informal settlements like Cape Town’s Khayelitsha. Alongside ETH Zurich and Ikhayalami, a local NGO, Urban-Think Tank developed the Empower Shack as a replicable, scalable affordable housing solution.

Innovation:

As part of the program, residents make meaningful contributions toward the cost of construction (14% of the total cost, available through microcredit loans) in exchange for a path to permanent tenure. Beyond housing structures, the project encompasses livelihood development projects, clean energy integration, and skills training for members of the community.

Using a 3D rendering software, residents are able to choose from a variety of housing configurations to suit their immediate and long-term needs. Because the constructions are multi-story and made of flame-retardant material, the Empower Shack utilizes space more efficiently while reducing the spread of fire.

Lessons:

A pathway to land ownership is a prerequisite for investing in any slum upgrade

Government-sponsored housing programs need to address a diversity of end-user requirements

Community structures need to be designed with incremental housing possibilities in mind

Potential in More Developed Countries

Affordable Housing

Empower Shack provides a model for land tenure that integrates end-user input into the design process (through use of open-source digital rendering tools) and an architectural framework that supports incremental housing upgrades.

NGOs like Pop-Up Housing in Bangalore, India, have developed a strategy for affordable housing that isn’t dependent on land tenure — the organization builds lightweight yet rigid housing frames from bolted metal angles that can be assembled — and disassembled — without special knowledge or tools.

In both cases, the approach to affordable housing is both bottom-up and top-down. In addition to providing infrastructure, the organizations offer livelihood and utility services to residents while acting as a bridge between local governments and community members.

A homeowner was able to finance a home for under $100K with a small-dollar mortgage (Image Source)

The US is facing a shortage of 7.3 million affordable rental homes. Assuming an average occupancy of five people per home, that figure is roughly comparable to South Africa on a per capita basis (one-twelfth of the US population vs one-eighth of South Africa’s). Rather than microfinance as such, small-dollar mortgages warrant consideration where low-income families are priced out of homeownership due to the mortgage amounts being too small for most banks to consider.

Rather than continue with the top-down model that relegates low-income households to multi-story housing projects, micro-mortgages for structures that can be incrementally upgraded would encourage community investment by residents themselves in the form of housing equity and neighborhood-level development.

Waste Management

With global municipal solid waste forecasted to increase by 70% to 3.4B metric tons by 2050, it will be increasingly difficult for developed countries to off-shore or landfill their waste. Despite widespread education campaigns in developed nations to segregate trash, the US only managed to recycle 5–6% of its plastic waste in 2021, with 85% ending up in landfills.

Unsafe and unsanitary conditions aside, Dharavi’s ability to recycle 80% of Mumbai’s plastic waste puts developed nations’ waste management numbers to shame. While incineration as a country-wide waste-to-energy approach has had issues in Europe, Kibera’s Community Cooker does well by assigning community ownership of waste as a resource within the energy production process.

Bottle return machines in Germany resemble vending machines, and dispense cash in return for recyclable items (Image Source)

Where the negative effects of consumerism are far removed from households in developed nations, governments might consider moving the recycling process — and benefits — closer to the consumer. Germany’s bottle-return machines are ubiquitously placed in cities (rather than a recycling facility on the city outskirts), incentivizing daily recycling through instantaneous remuneration with minimal burden to the consumer.

Community waste-to-energy infrastructure might also include decentralized, neighborhood-level plastic pyrolysis or biogas conversion plants. The American Biogas Council estimates that biogas could produce 103 trillion kilowatt hours of electricity each year, and offset carbon emissions equivalent to 117 million passenger vehicles. A neighborhood composting program could produce compost while converting methane from anaerobic digestion into energy, benefitting households directly through energy sales back to the grid.

Africa’s first grid-connected biogas plant in Kenya (Image Source)

Community-Owned Utilities

Through relentless grit and dogged persistence (not to mention dire need), Neza’s community organizers demanded, and eventually received, basic utilities where the government failed to provide them. Led by the Orangi Pilot Project, Orangi Town’s residents discovered the cost of self-implementing a sewerage project was less than a quarter that of private contractors.

USAID supports mini-grid projects in developing countries where local governments fail to establish a functional national grid. And yet on the homefront, publicly owned power grids are cheaper than the majority private alternatives.

Solar micro-grids are relatively common. Unlike biogas, however, solar cannot be used for conventional cooking or heating systems in cold climates (Image Source)

Combining the aforementioned waste-to-energy methods (biogas, plastic pyrolysis) with a publicly owned micro-grid could serve as a feasible path forward for developed nations like the US seeking energy independence with an adherence to net-zero norms.

G20 countries subsidize Big Oil to the tune of hundreds of billions per year. A fraction of that might be able to establish feasibility for a waste-to-energy model that places energy production, and waste management to an extent — directly in the hands of communities themselves.

Conclusion

Slums develop as a byproduct of urbanization — as was the case in more developed nations since the Industrial Revolution. Logistics aside, resettling slums doesn’t make sense — slums communities offer a valuable contribution to cities’ economy and core maintenance in the form of labor and waste management services. Beyond that, they have historically demonstrated a capacity to solve problems municipalities still struggle with.

Their innovation is made possible through material necessity and a lack of regulatory restriction. The result is both positive and negative — it allows new ideas to be tested, though too often at the expense of health and safety. Following a simultaneous top-down, bottom-up approach, the cities of tomorrow might realize a more equitable version of development by supporting these communities (while granting them a limited form of regulatory independence) while working to upgrade their living standards in pace with development plans.

In the global North, trickle-up innovations expose a peculiar irony. Developed nations purport to lead the charge in the net-zero crusade, creating the infrastructure for a new green economy focused on clean energy, renewable materials, and closed-loop waste management systems. And yet, the sheer amount of regulations — from installing solar panels to recycling plastic waste — still stands in the way of green energy adoption at a grassroots level.

While a regulation-less society would certainly be ill-advised, it’s time for national and municipal governments to conduct a more comprehensive audit on the value of these regulations in the face of more looming, climate-related concerns.